Sankara (print, presumably from Ravi Varmar’s studio, early 1900)

Indian Philosophy

The Axial Age

The German philosopher Karl Jaspers has characterized the period of the 6th to the 2nd century BCE (before the common era) as the Axial Age. This is a period of the establishment and flourishing of new worldviews that began to replace the polytheistic religious views that were dominant before that time. Many significant figures for the development of worldviews that were determinant for two thousand years lived at this time. In Greece, we see the early natural philosophers, as well as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle (who for their part go on, along with the Old Testament prophets of this period, to strongly affect Christianity). In India, we see the formulation of the philosophical ideas in the Bagvad Gita that serve as the foundation for the later developed Advaita Vedanta. We also see Buddha challenge the Hindu ideas that he inherited. In China, Loazi (the founder of Taoism) and Confucius (the founder of Confucianism) begin to develop their philosophical systems. In each case, systems of thought are developed that are generally viewed as more encompassing than those they came to replace. Our focus here is on Indian philosophy that has its roots in developments of this time — both Advaita Vedanta and Buddhism.

Advaita Vedenta

Indian philosophy is of course multifarious. Here we will only survey some basic ideas of the school of Indian philosophy known as Advaita Vedanta. This philosophical school was developed by the philosopher Shankara in the the eighth century of the common era. Yet it draws on ideas in the Upanishads and Bhagavad Gita, sacred texts within the Hindu tradition, the latter of which was developed in the Axial Age. Advaita Vedanta is particularly important for its clear expression of pantheism, the idea that there is one thing and that thing is God. Hindus view everything in the world as ultimately an expression of one underlying godhead.

While the main forms of Hinduism are pantheistic, Hinduism generally also accepts that one can speak of a plurality of gods. Hinduism generally acknowledges hundreds of thousands, or some say even millions, of gods. Yet the entire Hindu pantheon can all be viewed as expressions of the same underlying godhead, Brahman. Hindus believe that one can worship any of them as a vehicle for Moksa, or enlightenment. Brahman can work through the varying guises. Given that Hinduism generally accepts that one can worship any of the various manifestations of the godhead, Hinduism is also known as henotheism. Henotheism identifies all particular deities ultimately with one ultimate reality and accepts that one may worship whichever manifestation one wants. As a rule, the proponents of Advaita Vedanta focus on seeing this philosophically however, and emphasize Brahman.

While this is already complicated, in fact the discussion of ultimate reality in Advaita Vedanta is more complicated still: Just as that pantheon can be identified with the one godhead, Brahman, so all different people and things in the world can ultimately be viewed as expressions of a single world soul, known as Atman. This world soul is the true Self underlying many apparently separate visages of individuals. So you and I and all others are actually expressions of this world soul comparable to how the manifold gods are really expressions of one basic godhead, Brahman. Ultimately in fact, yoga (in any of its multiple forms that allow a binding of the individual to the godhead) will unveil that Brahman and Atman are also really unified. In other words, those forms identified with transcendent Brahman (the pantheon of gods) and the individuals of the world (viewed as expressions of Atman) are themselves really one thing. This too is called Brahman. Rightly understood, the transcendent and the immanent aspects of the godhead are seen as unified: Brahman and Atman are the self-same. Advaita Vedanta also of course has well-known views about the soul and its possible reincarnation and posits laws that control the transmigration of the soul–karma. These ideas will be expanded on later, as we also consider philosophical conundrums of pantheism.

One of the most serious questions arising from Hindu pantheism involves ethics: For example, if all individuals are really an expression of the one godhead, of Brahman, then what ultimate importance do moral ideas possess? If they slayer and the slain are one and the same, as is famously said in the Bagvad Gita and the Upanishads, then how do we really make sense of moral command not to kill? (Shankara’s commentary, addressing this and other issues, on some of the Upanishads can be found online.) Other questions concern what evidence is really sufficient for showing that there really is only one substance, Brahman, and that our sense of individual existent entities is ultimately illusory? What evidence, too, is strong enough that we might believe that there is a soul and that reincarnation really occurs? Other questions of the afterlife also present themselves: Sri Aurobindo, a premiere Indian philosophers of the 20th century and the developer of Integral Yoga, has asked what real consolation a belief in reincarnation provides for individuals given that it is not the individual self as we normally understand it that is reincarnated. If a man named John in one life is reincarnated as Leslie in a future life, there is in some sense no more John. Leslie will not generally have memories of having been John. John’s body will not exist, etc.

Of course, the discussion here of this as “Hindu philosophy” is oversimplified. There are minority positions within Hindu philosophy, like the Dvaita Vedanta, that are not monistic, such as the Advaita Vedanta I have discussed here. Proponents of Dvaita Vedanta are dualists who maintain that in fact the godhead, the world, and the individuals in the world exist as separate substances. They focus also on personal worship of Vishnu. Here, though, I focus on the main philosophical tradition of Hinduism.

Buddhism

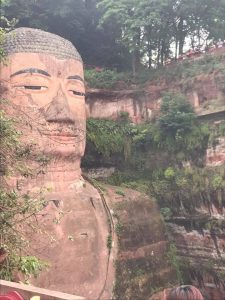

Giant Buddha (Szechuan, China)

Buddhist philosophy originates with Siddhartha Gautama, who becomes known by the honorific title, the Buddha. The Buddha’s life itself weaves an interesting philosophic narrative. According to tradition, he was born the son of a king in the Magda empire of Ancient India or present day Napal. He was raised a prince, but eventually turned away from the life of politics that his father had envisaged for him in order to pursue a life of spirituality. Specifically, according to legend his father attempted to shield him from seeing the troubles of the world. But on various occasions, the young Siddhartha left the princely castle and escaped into the streets of the city where he saw those who were ill, who grew old, who died, and finally a monk. Seeing this suffering and the monk who seemed to have avoid some of it, Siddhartha felt compelled to seek a spiritual life. He then left his home to join wandering mendicants and try to achieve spiritual enlightenment.

The sixth century was a tumultuous time, with many religious reformers who were dissatisfied with traditional Hinduism. Buddha, not himself a member of the priestly class or the Brahmin, joined these reformers, questioning the focus on the priestly class within Hinduism and more generally its strong caste system. In his search for enlightenment Siddhartha initially engaged in strict asceticism, denying himself many of his bodily needs. But he is thought by adherents to eventually have achieved Enlightenment, after having long meditated under a Bodi tree.

The Middle Way

One of the Buddha’s first proclaimed truths was the importance of “the Middle Way,” which states that it is not the life of excess (such as he enjoyed as prince) nor the life of ascetic denial (which he attempted in his early spiritual search) that leads to enlightenment. Rather, it is the middle path that neither indulges nor denies basic needs. Buddha presented some of his basic teachings in his first sermon, to monks with whom he had practiced asceticism but who were drawn to him after believing he achieved enlightenment. In that talk, known as the Deer Park Sermon, besides describing the Middle Way, Siddhartha (who now was given the honorific title of the Buddha, the awakened one) also presented his views of the four noble truths and the eightfold path, two of the most fundamental teachings of Buddhism, accepted by all Buddhist practitioners.

The four noble truths

The four noble truths outlined in this sermon are 1) that life is fundamentally characterized by suffering (dukkha); 2) that the cause of that suffering is attachment or craving (tanha); 3) that suffering can be overcome by the elimination of craving; and 4) that there is an eightfold path that makes it possible for us to eliminate this craving and thus eliminate suffering.

The eightfold path

This eightfold path consists of 1) right understanding; 2) right thought; 3) right speech; 4) right action; 5) right livelihood; 6) right effort; 7) right mindfulness; 8) right concentration. It is through the cultivation of a disciplined spiritual, ethical practice that one is relieved of attachment and one overcomes suffering. These various components of thought, behavior and concentration work in concert to allow individual liberation.

The three marks of existence

Metaphysically, Buddha also went a different path that his Hindu forebearers. While the Hindu thinkers emphasized the unity of all things in Brahman, a world substance that many of them thought to be permanent and unchanging, Buddha proposed a view of reality that continues to change and along with it a view of “no-self.” Where the Hindus focused on a unified “being” that encompassed all things, Buddha focussed on emptiness and non-being. All things, he emphasized, were in a state of constant change. The self, too, then is not “Atman” (Self, with a capital “S” or world soul) but “Anatman” (no-self). As some Western philosophers have expressed this idea: If an object changes from moment A to moment B, then how can that object be characterized as the same object at those two times? Is it not rather two different ones? Buddha himself highlights how at any given moment the mind is aware of a sensation, a thought, a feeling, etc. These sensations, feelings, thoughts, he views as “aggregates.” Where is the self behind all of these? The awareness we have is not of a self, but rather of one of these aggregates. With considerations like these, Buddha develops a considerably different metaphysics than one finds in the Hindu worldview that he grew up with. He speaks of three marks of existence that set his views apart from traditional Hindu thought: impermanence, no-self, and suffering.

Some common questions

Buddhism too raises numerous philosophical questions: For example, if the doctrine of the “no-self” is true, then what sense do moral commands to individuals have? Who is to carry them out? Who is responsible if there is no-self. And how are we to make sense of the goal of liberation or enlightenment if there is no self to be liberated or enlightened?

Buddhists, of course, have ways of addressing such concerns. Buddhists will of course acknowledge that as a practical matter, we will continue to refer to the self, use the words that reference the self, like “I,” “me,” “mine.” Yet this self is not thought to have ultimacy. This language, while needed for practical life, does not, for that, indicate that there is a permanent or separate self.

Co-dependent arising

The idea of no-self is tied to the Buddhist idea of “co-dependent arising.” That teaching, as we might express it in relationship to certain ecological ideas today, emphasizes the interconnection of all the conventionally understood self with the conventionally understood world. For example, though we might think of the boundaries of our skin as the boundaries of our self, in fact, we breath in air continually. We need the resources of water and food. Cut off from those things, the self disappears. So, we might wonder, can we adequately consider the self as cut off from the world around it? Without the oxygen, produced by the plants, we will expire. Without water for several days, we also die. The self is tied into and co-dependent upon these other things. So we might think of those things too as only conventionally existent. For they, too are dependent on other things, which undergo change from moment to moment and do not retain a permanent existence. What we have, though, is always only the happening of each moment, itself continually undergoing change.

Some similarities between Hindu and Buddhist thought

In some general way, philosophers of the Hindu and the Buddhist traditions that we have discussed here display similarities. Both emphasize interconnections. Yet, while Hindu philosophers speak of the individual self as part of a larger “Self,” a kind of Superorganism in which each individual is like a cell, Buddhists question that there is some overarching “Self.” They emphasize instead that all processes are undergoing change. They emphasize emptiness and nothingness rather than “Being.”

Yet other elements of these systems of thought are similar. Both traditions emphasize the need for adherence to a quite similar moral code and the need for a set of spiritual practices in order to achieve an intuitive awareness of metaphysical truths. They both generally accept the idea of reincarnation, and that the form of one’s reincarnation is dependent on how one has lived in previous lives — that is, they accept the reality of karma. Finally, the both accept the goal of enlightenment, even if they think that enlightened individuals understand the ultimate reality differently in these two traditions.

This conversation is only hinting at some of the philosophical issues at play in Hindu philosophy and Buddhism. Various concepts described here are also understood in other ways. And it is important to bear in mind that these worldviews are not static or uniform. In fact, we find various Hindu and Buddhist philosophers, all with subtle differences in how they understand their own traditions. These are rich thoughtful systems of thought, which each contain thinkers who debate issues with each other and with the traditional bodies of knowledge acknowledged by their traditions.

Some basic questions

Questions of course abound. Many of those posed when discussing Hinduism apply to Buddhism. Some of the following apply to both worldviews:

- Why should we accept that there is anyone who can be fully enlightened and that enlightenment comes through a spiritual practice rather than analytical thinking?

- If there is karma, why do so many good things happen to bad people and bad things happen to good people?

- Is the evidence that this is somehow related to past lives in any way convincing, or does it function as an ideological foil?

- Are these spiritual systems too focused on individual mental liberation and do they short social justice concerns?

- Are these systems ultimately overly pessimistic? Is individual life so oppressive and disappointing that we ought desire to escape the cycle of existence?

- Finally are basic elements of these systems of thought self-contradictory?

It is not only Western philosophers who have asked these questions. Hindu and Buddhist philosophers have asked themselves these questions. And they have attempted to address the concerns. Here only the broadest of outlines of these systems of thought can be introduced.