While Francis Bacon is very important for his advocacy of experimental science and his empirical leanings, John Locke (1632-1704) is very often considered the father of British empiricism. If Locke fails to make as significant of a contribution to the experimental method as Bacon, he nonetheless succeeds in offering a sophisticated view of human understanding that is taken up by George Berkeley and David Hume, the major British empiricists after him. Locke’s stature is enhanced further, though, by the great influence of his writings on social contract theory. His support of limited government and human rights had a significant impact on the Founding Fathers of the United States. Locke’s political philosophy will be taken up elsewhere. His epistemology will be highlighted here.

Locke’s most important contribution to epistemology is his Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Like Descartes in the rationalist tradition, and Berkeley and Hume in his own, Locke shifts his focus toward the mechanisms of human understanding. His epistemology represents a move away from the simple realism of the Aristotelian tradition. He focuses on the powers of the mind at work in the knowing process. One of Locke’s motivating concerns is that traditional scholastic epistemology had pushed beyond “our capacities.” Consequently, epistemologists had ended up embroiled in disputes about which no clear answers could be provided. He sets more modest goals than the Scholastic philosophers that preceded him and the rationalists who were more dominant in Continental Europe.

In contrast to the rationalists, who argue that the mind has innate ideas, Locke posits that the mind is at birth a blank slate. All knowledge has its root in sensory experience. There are two basic sources for this knowledge: One is our external senses, through which we come to experience the world. These are the ultimate source of all our knowledge. The other source is inner reflection. That is, we can consider the workings of our own minds, the ideas we have generated and so on. Locke’s view of epistemology is often called a copy theory or a representational theory. He maintains that the mind duplicates copies of ideas from the world. Yet this should not be understood simplistically. Our minds are passive recipients of what Locke calls simple ideas, things like color and shape. However, once in possession of such simple ideas, mind actively combines them into more complex ideas. So we are passive recipients of the simple ideas of roundness and orange-ness and juicy- and tangy-ness, but we actively generate the complex idea of an orange. This view that the mind combines simple ideas into more complex ones is sometimes referred to as a corpuscular theory of mind.

One of Locke’s first steps in the essay is to lay out his view that the mind is at birth a tabula rasa, a blank slate. Again, here he differentiates himself from the rationalists. He maintains we are not born with inscribed ideas — say of God, the self, or key logical concepts. Nor are we born with foundational principles of mind or even practical moral principles. Locke’s basic argument is that if such basic ideas were innate, then babies and the learning impaired should be able to articulate them. But they clearly cannot. Hence we must not have such innate ideas. The theory already outlined builds on this: All knowledge begins with experience. We passively assimilate simple ideas from that experience. Our mind’s then can actively go to work on those simple ideas, making more complex ones.

In light of the basic view that the mind is a blank slate, one must wonder where the active capacities of mind he discusses come from. He doesn’t adequately deal with this question. He does though write about three basic capabilities of the mind that he does not adequately explain the origin of: (1) The mind is able combine simple ideas into more complex ones. For example, it can generate an idea of an orange from its parts (i.e., roundness and orangeness, etc.). (2) It is able to compare ideas — that is it can compare an orange with an apple. For example, we can note that one is orange and tastes better when peeled. The other is typically red or yellow and tastes fine without peeling. (3) It is also able to produce more general categories of ideas from specific examples. For example, it can develop a category like “fruit” that includes both oranges and apples.

Another important distinction in Locke’s epistemology was commonplace at his time — namely that between the primary and secondary qualities of an object. The primary qualities are thought to inhere in the thing. As Locke sees it, these are the only real qualities. The secondary qualities are produced by the object but are not inherent to it. So the solidity, size and shape of the orange are primary qualities. But tastes, smells, and other perceptive qualities that are part of the experience of the thing are not primary and have a lesser ontological status. The sweet taste that I experience when eating the orange is a secondary quality.

There are many further dimensions to Locke’s epistemology. But this provides some basic building blocks. Locke clearly understands his view as a form of philosophical realism. However, others question whether he is correct about this.

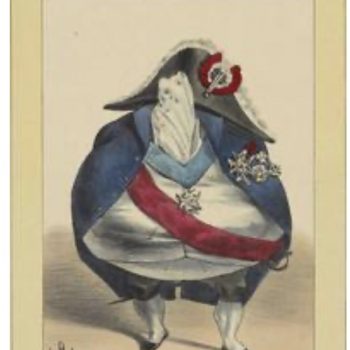

Bishop George Berkeley

Bishop George Berkeley was one of the first to question whether Locke, if read consistently, should not rather be understood as an idealist. He is one of many who have read Locke as having a representational view of knowledge. This means that when we perceive something, like an orange or an apple, what we experience is not the real orange or apple in the world but the idea of the orange or apple that our minds create. If this is correct and the referent in knowledge is to the ideas of the objects rather than to the objects themselves, then Berekely wonders, do we end up trapped in a world of mere ideas? This is weightier still, in Berkeley’s view, because Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities is untenable. While Locke maintains that only the primary qualities of a thing are real, and the secondary qualities are merely mental, Berkeley argues we cannot think of objects in reference to primary qualities alone. If we only think of qualities like the dimension and mass of the orange, for example, then we never think of the orange at all. To think the orange or any other such object, we must think of the secondary qualities as well as the primary ones. In Berkeley’s view, our experience is always of our mental representations of things.

With arguments such as these Berkeley proposes a form of empirical idealism — that is, the view that our ordinary experience is of ideas not things. “To be is to be perceived,” he famously says. Our experiential world is the product of mind. This leads Berkeley into a complex metaphysics, in which he argues that God is ultimately the perceiver of all objects. All of reality is thought. For more on Berkeley check the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

We shall now proceed to Hume.