John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) grew up in an extremely intellectual environment in London. His father, James Mill, was an early utilitarian and great friend of Jeremy Bentham. Under pressure from his father and Bentham to excel and learn, John Stuart Mill spent hours in study even as a very young boy and was deprived of many of the joys of a more normal childhood. His later battles with depression in part are related to this early intense experience. The experiment, then, as Isaiah Berlin noted, was “an appalling success.” Mill had composed a book on Rome by six, could read Plato in Greek by seven, and he was immersed in studies of Aristotle’s logic by 11. Of course, he was also early schooled utilitarianism. He accepted the philosophy but underwent an emotionally tumultuous break with Bentham’s views of it at the age of 20. Over time though he developed a more sophisticated version of utilitarianism than Bentham had, addressing many of the issues philosophers had raised about Bentham’s version. In Utilitarianism (1863) Mill proposed a form of utilitarianism that, in contrast to Bentham’s, recognizes a hierarchy of pleasures. It moves toward a view that we need to act on certain rules that in aggregate generate more utility rather than continually considering what creates utility in any given situation. It ultimately even affirms a form of virtue ethics, but based in the utilitarian reasoning that the society will be happiest in which individuals are routinely and habitually virtuous. In addition to this, in his book On Liberty (2859) Mill formulates the “no-harm principle,” which becomes a standard-bearing concept at the heart of liberal societies.

In part, Mill’s departure from Bentham’s utilitarianism is motivated by a more complex decision theory. Indeed, the psychological presuppositions of Bentham’s decision theory that Mill questions are unrealistic in the extreme. According to Bentham, in each particular situation, we must weigh what action results in the greatest good. This requires a calculus of immense magnitude, which entails a huge number of questions: Do I try to satisfy only my present happiness or also my long-term happiness? How much weight do I give possible future desires? How much weight do I give potential changes to my preferences? Doing the calculations would require mammoth powers. It would require listing for each activity how much we prefer which outcome, how much others on the whole prefer it, whether it is a short- term or a long-term preference, for whom, etc. We simply cannot decide anew in every situation what to do, weighting all-too-often-changing preferences. Were we to try, our action would be completely ineffectual. Mill rejects this view and argues, similarly to psychologists now doing work on decision-theory, that we act according to some guiding principles as well as habits and routines.

While there is dispute among scholars about whether Mill is a thoroughgoing “rule utilitarian,” there is much that points toward viewing him as one when that term is defined as determining how we decide upon our moral obligation. As he says,

According to the Greatest Happiness Principle (…) the ultimate end (…) is an existence exempt as far as possible from pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments, both in point of quantity and quality; (…). This, being, according to the utilitarian opinion, the end of human action, is necessarily also the standard of morality; which may accordingly be defined, the rules and precepts for human conduct, by the observance of which an existence such as has been described might be, to the greatest extent possible, secured to all mankind; and not to them only, but, so far as the nature of things admits, to the whole sentient creation.

Under normal circumstances we thus don’t ask from case to case whether we should lie, cheat or steal. We simply follow the general rule that we should tell the truth, be honest and respect people’s property, because when such rules are adopted we achieve the happiest kind of society. Indeed, as earlier noted, Mill even advocates for cultivating virtuous habits, so that the typically good action becomes a matter of course, not a calculated assessment. On the basis of the focus on long-term consequences of types of action, we can and should develop characters that respect many of the traditional moral actions.

Mill even emphasizes the need for a good will to facilitate good action. Such a will is formed under the tutelage of habits. “Will is the child of desire, and passes out of the dominion of its parent only to come under that of habit” (Utilitarianism, 294). Since we are creatures of habit, and not natural calculating machines, it is important that we develop good habits and develop a good will. By cultivating “habits of the will,” we then come to act in individual cases irrespective of pleasure (merely because of our habits). Since we develop these habits, aiming at happiness, they are not a good in themselves; yet they are to be cultivated, because achieving such habits “imparts certainty,” making it possible for people to rely on one another’s feelings and conduct (Utilitarianism, 294ff.). In general, individual virtue increases collective happiness because it leads to an increase in the number of good acts and appears itself to entail a higher kind of pleasure.

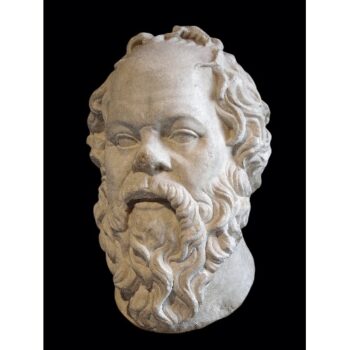

In moving toward a utilitarian virtue ethic, it is important for Mill to differentiate between kinds of pleasure. In contrast to Bentham, who proposes amassing the greatest quantity of pleasures, Mill proposes amassing the best quality pleasure. He distinguishes between lower carnal pleasures, on the one hand, and higher intellectual ones, on the other. As with questions of aesthetics, on the question of which of these pleasures are preferable: “the judgment of those who are qualified by knowledge of both…must be admitted as final” (Utilitarianism, 261).17 Or, as he adds, if there is dissent, then the judgment of the majority of those who have knowledge of both is to be accepted. Yet, he expects little dissent. It is “an unquestionable fact” that those who have tasted both prefer the intellectual pleasures (Utilitarianism, 259). This, too, is the reasoning behind his celebrated quote: “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides” (Utilitarianism, 260). In these statements, Mill is responding to John Carlyle’s early ridicule of Bentham’s view that all pleasures were equal, and his characterization of utilitarianism, then, as “pig’s philosophy.” Mill disagrees adamantly, noting that people would not willingly change fates with a satisfied pig nor the wise change fates for that of satisfied fools.

While happiness is the basis for moral theory, and the original motivation to be moral, in developing his position Mill generates a paradox. Achieving happiness, he argues, requires that we develop dispositions to do what is good for itself and that we come to desire virtue for itself: “The mind is not in a right state, not in a state conformable to Utility, not in the state most conducive to the general happiness, unless it does love virtue…as a thing desirable in itself…” (Utilitarianism, 289). While we have no natural inclination to virtue, we develop one. Then it “is desired and cherished, not as the means to happiness, but as a part of…happiness” (Utilitarianism, 290). In contrast to money and various other goods that can at some point come one into conflict with the general happiness of society, virtue cannot result in such a conflict. So it can be unconditionally supported, and is “above all things important to the general happiness” (Utilitarianism, 292). Like Aristotle, to those who do not see the higher value of intellectual pleasures and the life of virtue, Mill can only recommend that they change their lives, that they begin to exercise intellectual powers, that they begin to practice virtue. They will then develop the ability to judge rightly. Here, too, insight into the deepest ethical truths requires living ethically. Only if people do this will they see that their own individual happiness does not conflict with the happiness of society. In this respect, Mill’s argument differs from Aristotle’s. His view is not that being ethical allows us to fine tune our understanding of what the greatest happiness principle call for in specific contexts. It is that we can only judge between egoistic and non-egoistic pleasures when we know both. By implication, to adequately make the general judgment about what the greatest pleasure consists in, we must live a virtuous life.

Mill does argue that people sometimes lose their desire to indulge the higher pleasures, for example, because of lacking the “time or opportunity” to enjoy them. Since this may also be because the society that they are living in is unfavorable to the cultivation of higher pleasures (Utilitarianism, 261), like Aristotle, he too is for social and political solutions to problems. In fact, he sees social arrangements as able to eradicate many of the greatest human ills: poverty, he thinks, can be “completely extinguished.” Tersely put: “All the grand sources…of human suffering are in a great degree, many of them almost entirely, conquerable by human care and effort…” (Utilitarianism, 266). Since the principle of utility is two sided, aiming to increase pleasure and decrease pain, the eradication of such human suffering is essential to politics.

As the means of making the nearest approach to this ideal, utility would enjoin, first, that laws and social arrangements should place the happiness, or…the interest, of every individual, as nearly as possible [my emphasis] in harmony with the interest of the whole, and secondly, that education and opinion, which have so vast a power over human character, should so use that power as to establish in the mind of every individual an indissoluble association between his own happiness and the good of the whole…(Utilitarianism, 286).

Mill views history as undergoing a development in which, through education, this idea is becoming increasingly widespread and in which a feeling is generated in individuals of “unity with all the rest…” (Utilitarianism, 286). If this development is perfected, the individual will not be able to conceive of his own happiness in exclusion from the happiness of others. He does underline that steps have been taken toward this disposition: “few but those whose mind is a moral blank, could bear to lay out their course of life on the plan of paying no regard to others except so far as their own private interest compels” (Utilitarianism, 287).

A final idea of Mill’s to be emphasized here will only be laid out briefly, namely the idea of the “no-harm principle” developed in On Liberty. In that work, Mill argues that the society that will produce the greatest utility is one that provides for the greatest individual liberties possible. Restrictive societies, which prohibit our free expression, will not facilitate happiness. This idea becomes a bedrock of liberal societies. However, as we can see in the shifting views about what should be allowed, there is not always consensus on what generates harm. During U.S. prohibition, alcohol was thought to cause such great social harm that it should be prohibited. After it was legalized, various drugs were prohibited that many will argue are less harmful than alcohol. In reference to same sex relationships, we have also seen historical shifts. While earlier generations felt compelled to condemn same-sex relationships for undermining the traditional family, which might break up a basic unit thought to be fundamental to the fabric of society, younger generations tend to find such arguments spurious and little more than rationalizations for prejudice. What people do in the privacy of their bedrooms is thought there own business and who they love, marry and share their lives with is generally thought by younger Americans to be the concern of those individuals themselves.